Yuki Konno

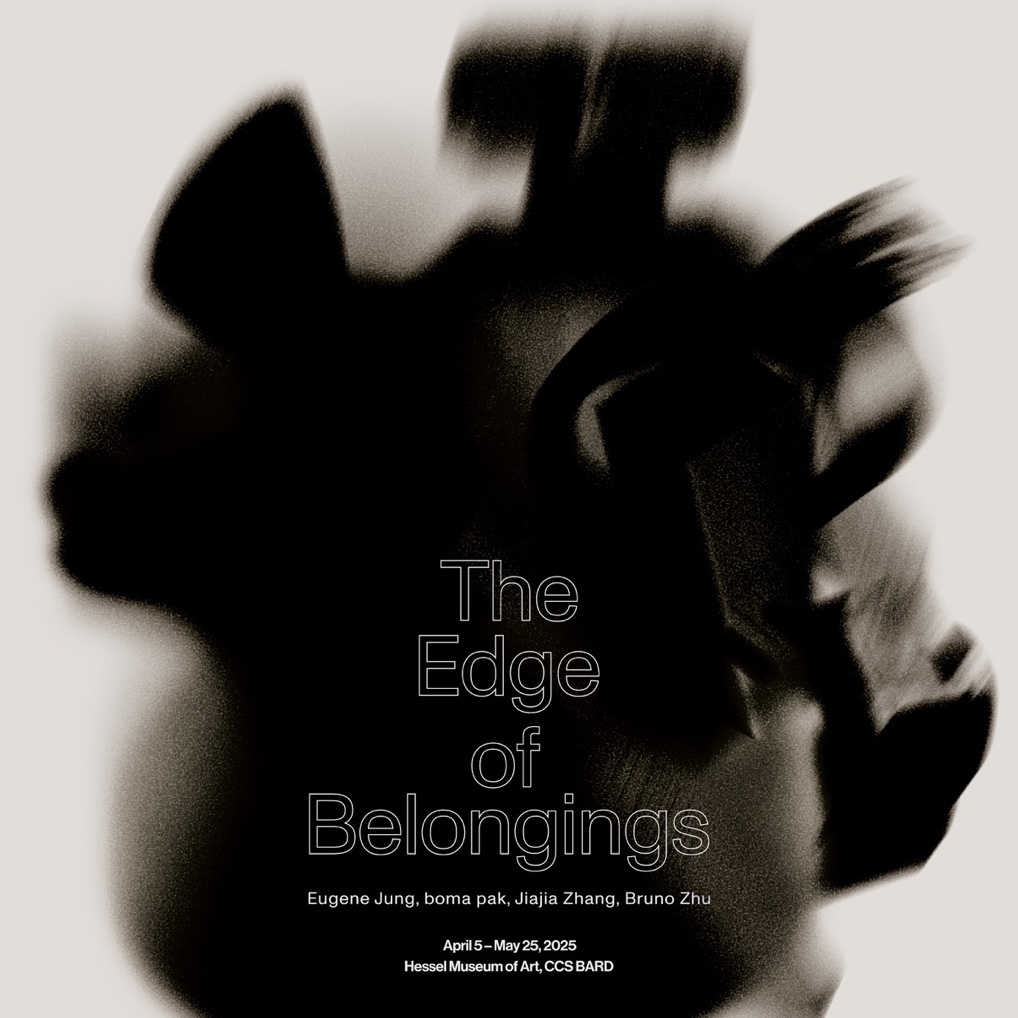

Eugene Jung, At least, Realistic(2019, Site of Chuohonsen Gallery) / Courtesy of the artist

A certain sense of distance is premised when the spectacle is consumed. Contrary to being dragged in when it actually happens in front of one’s eyes, people can handle shocking images by securing a sense of distance. In those moments, the objectified images can be approached for entertainment, and people can actively be immersed and then pull out of it. As spectacles that can be experienced only ‘visually’ like movies and videos and recent VR (Virtual Reality) providing a quasi-experience, the way of experiencing objectified scenes makes the viewers viewing experiencers from actual experiencers by securing the distance. Shocking scenes seen through photos or videos are viewed from a distance from reality. When the screen is turned off or the device is removed, the viewing experiencers recognize that it is fake or a copy of reality. The distinction between the two is very vague and indistinguishable. Spectacles are delivered without being easily distinguishable whether it is news or a movie scene. No matter how much the traffic accident footage on YouTube contains real noise than the murder video edited by ISIS(Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), the reality beyond the screen or photograph generally stays in the media, not the experience of the reality itself. Whether it is a video (footage) derived from reality or a scene of a virtual world collapsing from the movies, it is not something one experiences in reality. It is just a difference in the sense of distance and the spectacle is not rooted in the here and now of one’s experience.

Eugene Jung, Cave art (2018, Audio Visual Pavilion) / Courtesy of the artist and AVP

The experience for viewing is reflected in the interests and work of artist Eugene Jung. The artist is interested in scenes of disasters and catastrophes shared with the public, including cartoons, and expresses them with thin and brittle materials. This characteristic is also true in the piece presented in the show At least, Realistic held at the site of Chuohonsen Gallery. The artist builds the ruins of the Great East Japan Earthquake that occurred eight years ago in the exhibition space with fragile materials (e.g., plastic boxes). In Eugene Jung’s work, light materials that are artificial or fake, weak, and not sturdy are often used. They can be divided into two main ways of expression. One is works that are created with a focus on stories. For example, in Doomsday Garden(2018) introduced in After 10.12(Audio Visual Pavilion, 2018) and Resurrection of Paul the Psychic Octopus(2019) recently presented at Doosan Art Center, the artist creates the works with reference such as a narrative or story as a starting point. Resurrection of Paul the Psychic Octopus(2019) is a work based on the documentary The Life and Times of Paul the Psychic Octopus(2012) that the artist watched. In the documentary, an aquarium in Germany raises an octopus to predict the outcome of the World Cup match and even a burial urn was made after its death. And as for Doomsday Garden(2018), it was produced with reference to the story of “Jo will become the king(주초위왕, 走肖爲王)” in the Joseon Dynasty. According to the story, it was believed that a prophecy came down from heaven which appeared as a phrase on a leaf gnawed by an insect. Both cases show the foolishness or ridiculousness of people’s attitudes toward some things and the artist also embodies predictions that have not been fulfilled and thus seem more ridiculous. Although not resurrected after its death, the imagination that Paul might be resurrected and the apocalyptic landscape imagined through the prophecy from heaven that says “The death of human beings is truly eco-friendly!” on a fake plant which is realized by a plastic-eating insect(robot insect?) unfold in those works.

In both works, the method of imagining ‘something that may happen in the distant future’ and showing it as a ‘prediction’ in the present is a characteristic common to Cave art(2018) and Growing gravestone(2018). The former records the current state of Seoul physically on Styrofoam, and the latter shows how the gravestone grows in two consecutive exhibitions (Superposition at Gallery 175 following After 10.12 at Audio Visual Pavilion.) In the first exhibition, Growing gravestone was placed on the floor of the space as if it were growing from the ground, but in the second exhibition, the height was raised by attaching metal rods as if it had undergone a life-sustaining surgery, rather than simply increasing the height with the original material. The strange premise that the gravestone grows is developed into a more complex form than a simple gravestone by adding other materials. Rejecting the completion of the work itself, as if rolling a dice resulting in 7 or an alphabet letter rather than in 1 or 3, the work shows the imagined possibilities that exist beyond the given condition (that is, the gravestone must be a gravestone).

This work also inherits the previous method of work in terms of materials but deals with the spectacle through the formative aspect rather than representing fables. This is the second characteristic. If the work described earlier took a prediction and showed it as a work, this exhibition shows an attitude of consuming/viewing the spectacle by paying more attention to the relationship between reality, its replica, and fake, as reflected in the exhibition title, At least, Realistic. The artist received about 20 gigabytes worth of images of the Great East Japan Earthquake ruins from a friend and created the scenery inside the exhibition space. In terms of production methods and interests, At least, Realistic is in common with the Phantom Mutant series(2018), which was shown at Gallery 175 in 2018. In Phantom Mutant, elongated cat and fox were created with paper in reference to a meme that has been circulating on social media, which was panoramic error photos that spread with a rumor that “There are these animals roaming around the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident area now!” In the case of this exhibition, it is common to Phantom Mutant in that the photographed image is treated with light materials. Not only that, but it is also common in that it captures the process by which the facts recorded in the photograph are moved away from their original time and space and understood differently, rather than predictively showing the future. The cat’s elongated body is misread as a symptom of a nuclear accident and the tsunami-damaged ruins are recognized as a movie set. Referring to this situation, the artist shows that the recorded image is implicated with reality/fact or floating between false or unrelated contexts. In this exhibition, the installed iPad next to the work allows the audience to see that the work was created based on the data. Numerous 20-gigabyte worth of ruin photos that can be viewed on the iPad approaches like a movie set and it oscillates between specific accident and the doubt of “Is it real?” In what sense are these images realistic? It represents reality in that it contains a certain scene as it is and has good resolution and quality. However, scenes that are not seen on a daily basis feel separated from reality to the viewers. Following the sense of distance that is premised when delivered as a record, it is difficult to easily distinguish whether it is a scene from reality, a production set on a real stage, or a fake.

The gap from reality means that neither space nor time is here now, which is closely related to the nature of the ruins (hereafter referred to as ruins) that the artist deals with. The spectacle deviated from the actual space is also separated from the recorded time and is subject to consumption. Temporal deviations also appear in the ruins. The ruins in the ‘here and now’ exist as indicators of the ‘past’. Turning back time, the ruins were not ruins in the past and that means the ruins were not born as ruins in the first place. The ruins that appear over time are spaces where people originally lived, but their functions are discarded and gradually decayed and collapsed. In relation to the Great East Japan Earthquake, they play a role as an indicator of certain events and damage. The ruins are deviated from time and space, appearing as the past, and shared as a spectacle through a sense of distance from the present moment. The ruins created in Jung’s work are created primarily through spatial distance/sense of distance, and secondly through the ruins separated from time. However, just as ruins are not born as ruins, her works do not create ruins themselves but are produced as if only by removing the skin or exuviae of the shared images. Although her installation overwhelms the exhibition space, her work is not as immersive as VR and is farther removed from reality than the video recordings of the tsunami and the photos on the iPad in the exhibition. Her attitude to recreate the ruins away from the axis of time and space in the exhibition space through this exhibition fails to create real ruins and makes the exuviae of ruins. This is the core of her work. In other words, the work focuses on pointing out the spatial and temporal disparity rather than enchanting with spectacles and immersing the viewers in the ruins.

적어도, 현실답게 / 작가제공

This work by Eugene Jung deals with the poor way images exist and reveals the fragility of recording through sculptures. The images of the tsunami-affected area referenced in her work serve as a record of real-time and space and an indicator representing the tsunami. But (as Krakauer foresaw earlier) the facts recorded here are interpreted as a trend, that is, decorations that no longer have meaning over time, when they become difficult to support. The fragility of records is the same not only for photographs but also for sculptures, especially monuments. Monuments that serve as indicators of an event are also supported by context. When recording traces of an actual event, its characteristics are more directly reflected, but in most cases, monuments are produced as indicators that remind of the event rather than the traces of the actual event itself, such as bullet marks. The artist shows the recordability of monuments through sculptures, but also reveals the impossibility of recording and conveying both photography and monuments. Photographs or monuments are created to record and convey the reality that occurred at a time, but they cannot be fully conveyed as they become farther away in space and time. If the attitude of recording the present in preparation for the end is in photography and monuments, Eugene Jung deals with ‘the end’. The work predicts and shows the collapse of the delivery. Although it can be recorded, the context deviates through transmission, and the weakness supported by another interpretation remains only as an image. Therefore, in this work, the status of preservation and recording is positioned not as a record of context, but as the weakness of passing images. She records neither a monument that records an event or a causal relationship as an index nor a photograph taken to record this place at this time, but an image that forms a different meaning when contexts deviate or are newly combined, that is, an image as exuviae that is gradually separated from real space and time. In that sense, Dustwall(2017) is not an image of brick taken from a specific context, but is interpreted as having context in the sense that it reminds of a specific event or image. It reminds us of the ruins of the Great East Japan Earthquake, but in this work, the artist finds the texture of concrete through an Internet search without any specific references and prints it out on paper. The texture itself is a material that can be easily found on the Internet, which can be found if you search while working on Photoshop or Illustrator and it has no original meaning. However, this work, which was piled up in the exhibition space and appeared in different forms from exhibition to exhibition, represents not only the material fragility and flexibility in its arrangement but also the poorness of the aforementioned image itself—which in some cases becomes an image that exerts intense power. Viewers can think of earthquakes or specific events by looking at the work, but the image leads to a different context even though the actual image has no meaning.

The poor image, which deviates from time and space and suffers from the absence of interpretation and the grant of interpretation, is consumed as a spectacle due to a further gap in the already disparate situation. What remains after this process? It is an image like exuviae. However, the image is misread and given a different context in a situation where it is difficult to determine what is real or fake, as is the case with the exuviae, and moves away from reality. Due to the existence of the photographs, the work At least, Realistic reveals reality, not a virtual stage as the image is supported by the specific context of the Great East Japan Earthquake. By showing the relationship between the arrangement of numerous photographs that are recorded materials and the works, the original-replica relationship, it shows that it is ‘still’ close to the real space and time. In relation to the following three elements: a specific real event, a photographic record showing the event as an index, and a work that recreated the event through observing the recorded image, the ruins of the Great East Japan Earthquake move farther away from the actual time and space and increasingly situates itself in an exhibition space in Nish-Ogikubo, Tokyo, where there was little damage from the event. At least, Realistic not only deviates from the time and space of reality according to the distribution and spread of images but also points out the (contextual) impossibility of an image and its impossibility to deliver it, barely showing reality through recorded materials as image exuviae that remains.